Discover The Lighthouse & Gardens

an ambitious ‘meanwhile’ project that mixes wellness and community activities in a striking urban setting

Most recent settlers of the plusher areas of Stratford and Hackney Wick might not yet have Stratford East on their radar, but it’s a theatre that this year is celebrating its 140th anniversary.

Concealed by shopping centres, high rises, and findable by a path of banners from Stratford station, the theatre stands its ground as a hub for socially and politically conscious performances, in particular those that evoke the spirit and issues of the local community.

Upon entering its doors, one is struck not only by its Victorian, East End charm, but also its avid displays of a rich and progressive history.

Running up the walls are photographs of its productions of groundbreaking plays like ‘Scrape off the Black’, which in the 1980s was a hard-hitting exploration of mixed-race relationships, as well as historic staging of classics like ‘Phantom of the Opera’, which was performed at Stratford East just prior to its adoption by Andrew Lloyd Webber.

There are also small, idiosyncratic details that add to the character: my seat was inscribed with the words: ‘Benjamin Zephaniah loves all’. There is even a plaque to the ‘Theatre Workshop Manifesto’, originating with the idealistic theatre of Joan Littlewood, who took over as artistic director at Stratford East in 1953.

Though the language is a little grandiose (‘we want a theatre with a living language, which is not afraid of its own voice and which will comment as fearlessly on society as Ben Jonson or Aristophanes did’), the aim of establishing a popular theatre ‘which will speak for the common people’ is certainly worthwhile.

The winds of this legacy can still be felt today in its schedule of high calibre musicals and plays, not least in ‘The Women of Llanrumney’, a show that continues the discussion of Britain’s role in the slave trade with an unsparing look at the brutality towards its victims.

The story is set entirely on the Llanrumney plantation, Jamaica, in the dark depths of the slave trade in the 18th Century. The plantation is failing because of fungal rot, and the decay of its proprietor Elizabeth Morgan (Nia Roberts), who is so repugnant it’s hard to identify which of the seven sins she doesn’t exhibit. Her slaves, Annie (Suzanne Packer) and Cerys (Shvorne Marks), debate their avenues to freedom while she tries a range of desperate measures to save her fortune.

Initially the tone is that of a dark comedy of manners, with Elizabeth reeling off a foul-mouthed monologue about a lack of sophistication on the island while her servant Annie placates her. There is humour, but it is strung by our bleak understanding that Annie has convinced herself of her status as a confidante to her white owner, and of her ‘privilege to work in the Great House of the esteemed Llanrumney Estate’.

Cerys, who broods effectively at the back of the stage while Annie serves the table, lambasts her as a ‘fool that don’t even know she’s a slave.’

All three women are played magnificently. Packer captures the strain and stream of years of oppression, which manifests in desperate pleas to Cerys to stop threatening her small zone of security. She gives perhaps the most potent moment of the play, with a monologue on the execution of her mother, who was put in a cage by the colonisers and hung from a tree to starve.

Here she delivers from Azuka Oforka’s scathing script, which proves the power of dialogue to conjure up horrifying images of atrocity. If there is a testament to social protest theatre, then it is here.

Marks is equally impressive as the burgeoning radical, who throughout the entirety of the play attempts to inspire defiance in Annie and burns with fervour over an incoming slave

rebellion.

The tension is sustained throughout, and the pivotal turn of Elizabeth from comic lady of leisure to ‘pariah in this parish’ is handled successfully and brings a terrible vengeance in the final act. I’ll save the spoilers here, but there comes a point in the latter stages where there are no more laughs.

The resonance of the play comes through the moments of displayed and imagined horror, and how women are betrayed continuously by exploitation and desperate claims to whatever power people can find. But the leaps to the modern age might have been committed more.

There are some aphorisms, such as ‘Rebellions aren’t just fought in battle y’know, they happen every time we connect and love each other’ and ‘Real freedom can’t be written on a piece of paper’, but the resolution feels a little thin.

Regardless, Stratford East continues to stake its claim in the orbit of the West End. And this tightly-wrought play performs nobly in reminding its audiences of the suffering upon which so much of this country is built.

The Women of Llanrumney is showing at Stratford East until 12th April 2025.

an ambitious ‘meanwhile’ project that mixes wellness and community activities in a striking urban setting

Creative Wick founder, William Chamberlain, on the steady growth of the Hackney Wick model of ‘inside out’ regeneration

The big summer music events in Victoria Park

It’s the place to find out how you can get involved in the big summer festival activity in Victoria Park

Cyclists want Caroline Woodley to make the borough even more friendly for two-wheeled travel

When an area changes as rapidly as Hackney Wick today, it can place a range of stresses on our wellbeing. But help is close at hand

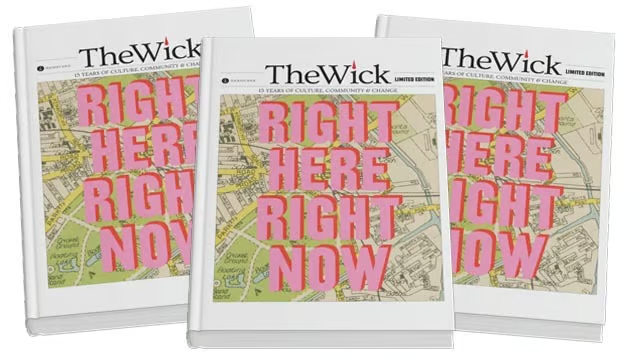

A 160-page hardback celebration of resilience, featuring hundreds of photos, stories and memories: 15 years of culture, community and change